The case that the historical

King Arthur might be the Dalriadic prince Artur, or Artuir, has

been re-examined recently. Ziegler (1999)

concluded that there is no compelling reason to believe that

this individual was Arthur. However, I argue here that a more

likely Dalriadic contender is to be found in the figure of King

Comgall, the grand-uncle of Artur mac Aedan.

Early

Individuals Known as Arthur

From the end of the

6th century a number of individuals were known as Artur or near

variants. Barber (1972) highlighted

the two most prominent - Artur of the Dalriadic Scots and Arthur

of Dyfed, but did not substantiate the case for either.

Ziegler (1999)

examined the first, Artur of Dalriada, but presented convincing

objections. The dates concur with her view: both these individuals

lived at the very end of the sixth century, and are unlikely

to be the historical Arthur.

Three sources provide

the earliest references to Arthur. The Welsh or Cambrian Annals

(Annales Cambriae) contain two explicit references: the

victory of Arthur and the British against the Saxons at Badon

in AD516, and his demise after the Camlann conflict in 537 (Morris 1980). The Gododdin, attributed to Aneurin, describes a

catastrophic defeat by the Saxons of a contingent from Edinburgh

at Catreath (Catterick) near Scotch Corner. The battle was in

around 570 (Koch 1997); the wording

suggests the warrior, Arthur, was of a previous generation, also

fighting against the Saxons - the Gododdin Arthur could

well be the same individual who fought at Camlann in 537.

Last, an account of Arthur's

many battles appears in the Historia Brittonum (Morris

1980). The battle list bears no dates, but the account also

tells how Ochta, son of Hengist, was instructed to fight 'contra

Scottos' in the North by the Roman walls, noting 'Arthur

fought against them at this time.' The Irish version of the

Historia states 'Ochta, the son of Hengist, assumed government

over them. Arthur, however, and the Britons fought bravely against

them' (Van Hamel 1932). Hengist

died in around 488, placing his son (or possibly grandson) Octha

at the beginning of the Arthurian period.

The story these three documents tell is consistent -- an Arthur

fought, in the early sixth century, against the Saxons on the

side of the early Britons, so ruling out the later Artur.

Locating

Arthur's sphere of activity

This does not exclude

the possibility that Arthur might be another member of the Dalriadic

Scots. Indeed, the evidence placing Arthur in North Britain is

strong. Skene (1876), Bromwich (1963), Goodrich (1986),

and Glennie (1988) all looked to

Arthur's battles as listed by Nennius and concluded that these

conflicts took place predominantly in the southern regions of

present day Scotland, with some in what is now northern England.

There are locations that cannot be identified readily, but four

have received a large measure of support.

The first is near Loch Lomond. Nennius tells of battles on the

River Dubglas in the region of Linnuis. This points to Lennox,

north of Glasgow. Dubglas is 'blackwater', and a river

Douglas flows into Loch Lomond. One battle was fought in the

Celyddon (Caledon) Forest, overtly Scotland. Another was on the

hill called Agned that twelfth century Geoffrey of Monmouth tells

us is Edinburgh. Finally, Goodrich (1986)

puts forward a strong argument that the Camlann site is at Camboglanna

(Birdoswald), a fort on Hadrian's wall. Each identification may

be open to challenge; together they provide a formidable case

that Arthur fought in the North.

The Scottish theme crops up elsewhere. As discussed by Glennie

(1988) and Goodrich (1986),

the highest density of Arthurian placenames is in Scotland: exemplified

by Ben Arthur, adjacent to Loch Lomond, and by Arthur's seat,

Edinburgh. Other, later, legends suggest that Arthur's sister

married the King of Lothian, the county of Edinburgh: Arthur's

warring in Southern Scotland and the Borders may need to be taken

seriously.

The Annales Cambriae

provide a second line of evidence as to his identity. I suggest

that, if the early scribes wrote of Arthur, they would write

also of Arthur's kinfolk. The Annals name ten persons over an

80 year span centered on the Arthurian entries. One is connected

with Wales - King Maelgwn. Excepting Arthur himself (and his

legendary nephew Medraut) the remaining seven entries relate

to Ireland. One, Gildas was a Clyde native who spent the last

years of his life in Ireland and, according to Caradoc's Vita

Gildae (Williams 1990), encountered

Arthur in person. Three were prominent Irish Christians of the

time. The last three are Irish Scots of the Dalriadic dynasty

that settled the western coast of Scotland.

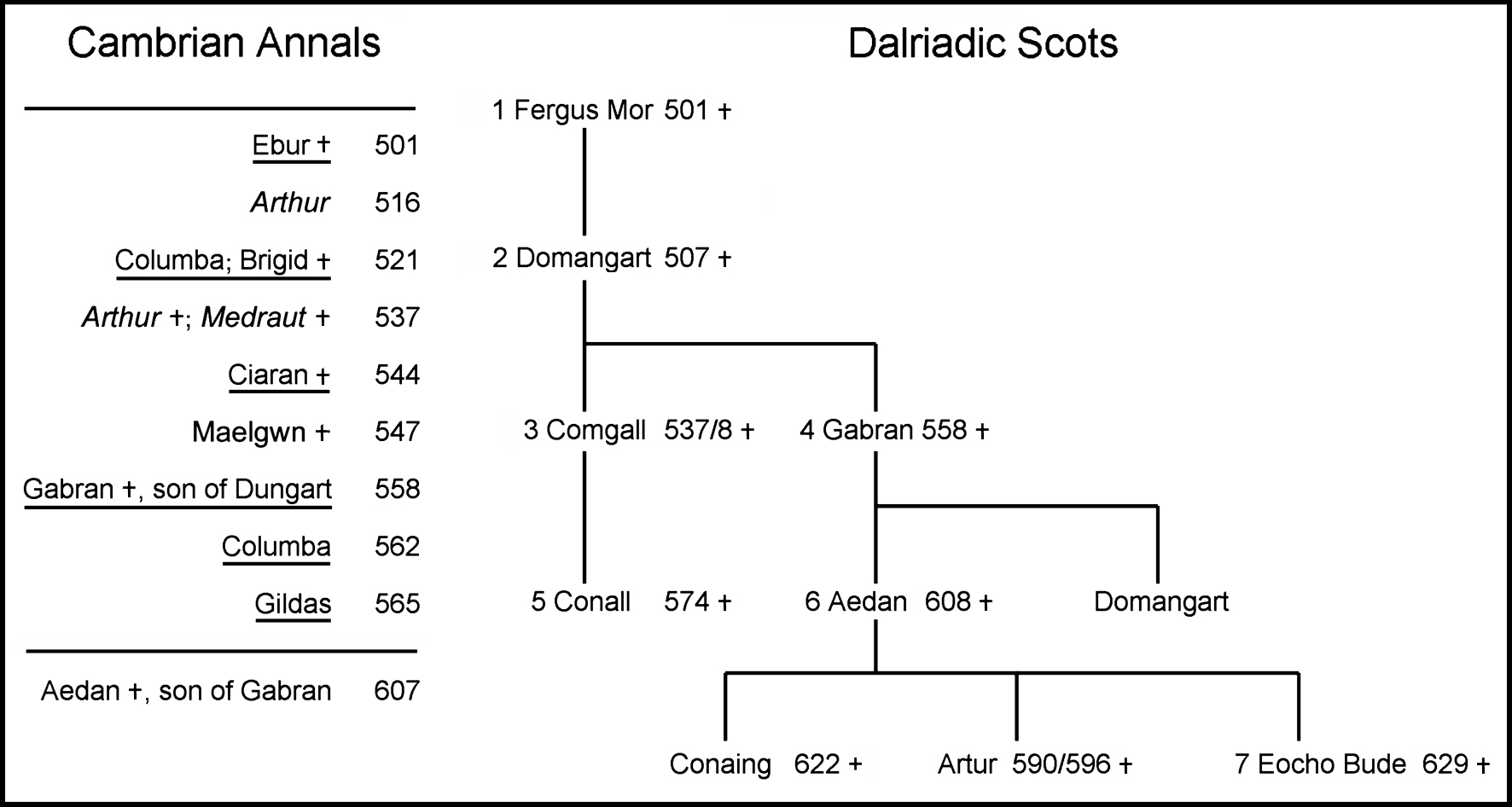

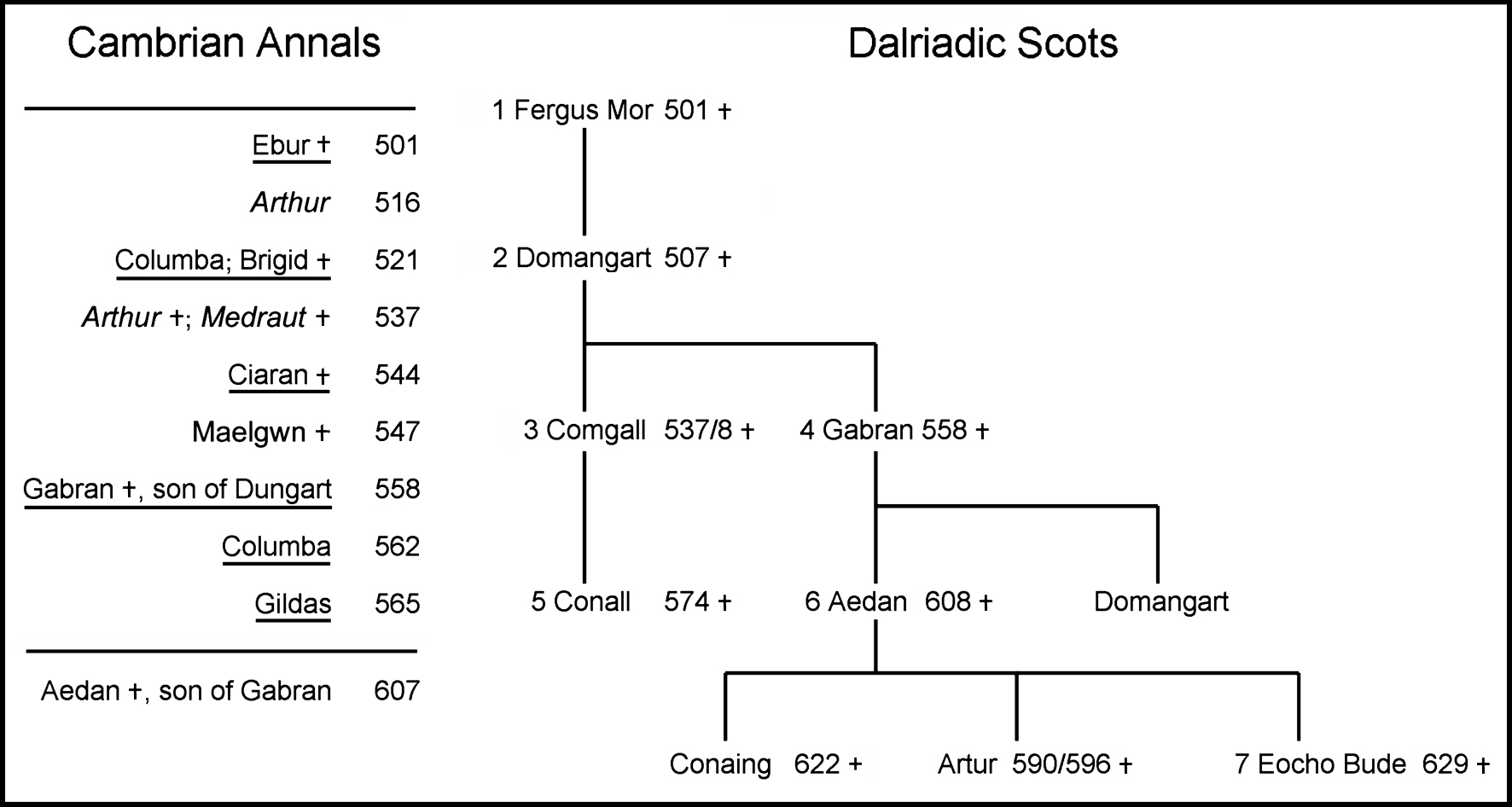

Figure

1. Left: Individuals named in the Cambrian Annals (Annales

Cambriae) in an 80-year period (486 to 567) spanning the

Arthurian entries: those associated with Ireland and the Irish

Dalriadic Scots are underlined. Right: Pedigree of the

Dalriadic Scots; prefixed numerals indicate the order of accession

to the throne; obit dates are given as suffixes.Click

here to enlarge figure.

Therefore, while the

earliest records point to North Britain, the flanking entries

in the Welsh Annals suggest a connection with Ireland and the

Scots. A possible point of overlap is in the warring activities

of the Dalriadic Scots in southern Scotland.

There is little doubt that the Dalriadic Scots were allied to

the British. Gabran married the daughter of Brychan, the founder

of the British kingdom of Brecheiniog (probably at Brechin, Forfarshire)

in Scotland, while Aedan is reputed to have been a grandson of

Dyfnwal Hen, the ruler of the British kingdom of AlClud (Dumbarton)

by Glasgow, and is said to have been born on the Forth.

Scots were active across the South of Scotland, and supported

the Britons in their conflict with the Saxons. Gabran lends his

name to the region of Gowrie, while the descendents of Aedan

were known as 'the men of Fife'. Aedan is recorded, by Bede and

other reliable sources, fighting alongside the Britons of Edinburgh

against the advancing Saxons. The Scotichronicon refers

to a Scots king Comgall, son of Domangart, who fought against

Saxon incursions in close alliance with the British (Watt

1989). Ziegler (1999) reviews

further evidence for Dalriadic activities in the south of modern

Scotland.

Arthur

and the Kings of Dalriada

The records pertaining

to the Scots contain no mention of an individual 'Arthur', with

the exception of the later Artur. I propose an explanation. Dalriada

is generally held to be a compound of dal (or dail,

'portion', 'meeting' or 'tribe') with Riada (Riadda/Riata),

as Bede opined, but this latter

may also be a compound of ri- (rig, righ, rix;

'king'), with Adda/Ata. Watson (1926)

informed us that Add, as in the prominent Dalriadic stronghold

at Dun Add (also Att), was pronounced, even until recently, Athd

with a long A. Therefore, ri-Adda may have been

pronounced ri-Athda. If so, the King of the Dalriadic

Scots might have been heard, by British ears, as Athda,

only a short way from airth (Welsh), 'the bear', and Arthur.

The Dalriadic Senchus Fer n'Alban (History of the Men

of Scotland) and other sources collated by J. Bannerman in

his Studies (1974) relate

that the throne was held by Comgall. Comgall's rule (from 507)

spans Arthur's exploits (Figure 1).

The Annales Cambriae, a primary source for Arthurian legend,

record the death of the historical Arthur in 537, while the obit

of Comgall is at 537/538 in the Annals of Ulster and Annals

of Tigernach. Thus, the dates of Comgall and Arthur accurately

coincide.

Conversely, the Annales Cambriae make no mention of Comgall,

an important leader, even though his brother, nephew and father

are there in name. The omission could make sense if Comgall was

Arthur. This could also explain the younger Artur born to the

Dalriadic dynasty at about the time of Comgall's death, perhaps

named in tribute to Comgall. Plausibly, the earliest historical

records suggest an identity for Arthur. Comgall, like Arthur,

fought against Saxon incursions in allegiance with the British.

Where the Annales Cambriae record the death of Arthur

(AD 537), the Irish Annals record the obit of Comgall (AD 537/8).

Although the later Artur has been ruled out (Ziegler

1999), I suggest that the Dalriadic Scots might have provided,

in the figure of Comgall, the model for King Arthur.

Works

Cited

Bannerman,

J. 1974. Studies in the History of Dalriada. Edinburgh:

Scottish Academic Press.

Barber,

R. 1972. The Figure of Arthur. Worcester: Trinity Press,

Worcester.

Bromwich,

R. 1963. "Scotland and the earliest Arthurian tradition".

Bibliog. Bull. Int. Arthurian Soc. 15: 85-95.

Glennie,

J.S.S. 1988. "Arthurian localities", pp. 65-120. In:

An Arthurian Reader. Matthews, J., ed. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Goodrich,

N.L. 1986. King Arthur. New York: Harper and Row.

Koch,

J.T. 1997. The Gododdin of Aneirin, Text and Context from

Dark-Age Britain. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Morris,

J., ed. 1980. Nennius, British History and the Welsh Annals,

Arthurian Period Sources Vol. 8, London: Phillimore.

Shirley-Price,

L., trans. 1968. Bede: History of the English Church and People.

London:Penguin.

Skene,

W.H. 1876. Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban.

Vol. I, History and Ethnology; Edinburgh: Edmonston and

Douglas.

Van

Hamel, A.G., ed. 1932. Lebor Bretnach: the Irish version of

the Historia Brittonum ascribed to Nennius. The Stationery

Office, Dublin.

Watt,

D.E.F, ed. 1989. Scotichronicon, Bower W, (1385-1449).

Vol. 2 (books III & IV), Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press.

Watson,

W.J. 1926. The Celtic Placenames of Scotland. Edinburgh:

Birlinn. 1993 reprint.

Williams,

H., trans. 1990. Two Lives of Gildas by a Monk of Ruys and

Caradoc of Llancarvan. Lampeter: Llanerch. See the Medieval

Sourcebook:"Caradoc of Llangarfan: The

Life of Gildas"

Ziegler,

M. 1999. "Artur mac Aedan of Dalriada". The Heroic

Age, 1: http://www.mun.ca/mst/heroicage/issues/1/haaad.htm