|

The Heroic AgeIssue 4Winter 2001 |

The ultimate age of the settlement at Bamburgh is unknown. Documentary sources tell us that it was originally a British settlement later conquered by the Angles. According to the Historia Brittonum (c. 830), it's original name was Din-Guaïroï [1]. Two further Irish sources may also record the name as Dún Guaire i Saxanaib, the destination of Fianchnae mac Báetáub in a saga title whose text has been lost, and an annal entry that records "Expungnatio Ratho Guali la Fiachnae mac Báetáin" [2]. According to the Historia Brittonum, Din-Guaïroï was added to Bryneich [Bernicia] by Ida, the reputed first king of the Anglian dynasty of Bernica. Bede dated the beginning of Ida's reign to 547, claiming that he was the founder of the Northumbrian royal dynasty. From the Moore Memoranda and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, we know that Ida is credited with a 12 year reign. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle claims that Ida built the first stockade and then the wall of the fortress, although this is unlikely as Anglo-Saxons of the period were not fortress builders. The stockade and wall referred to were likely built by the British. The first Anglian king to appear in the historic record with any confidence is Æthelfrith, grandson of Ida, who ruled from c. 592-616. It was against Æthelfrith that the expeditions recorded among the Irish were targeted. According to the Historia Brittonum, Æthelfrith gave Din-Guaïroï to his wife Bebbab, from whom it was named Bebbanburh [Bamburgh]. Bede's Historia (III.6, III.16) also claims Bamburgh was named for Queen Bebbe, although he does not name her husband. The rediscovery of the cemetery at the base of the Bamburgh fortress is the first surviving archaeological proof of the transition between the British and Anglian inhabitants of Bamburgh.

MZ: Before we talk about the cemetery, can you tell us who is involved in the Bamburgh Castle Research Project and what is the scope of the project?

GY: There are three Project Directors, Paul Gething, Philip Wood and myself. We all work in commercial archaeology in the north of England. The project is centred on the castle site but its scope includes the surrounding landscape. As a defined limit we have used the extent of the medieval unit of 'Bamburghshire'. This extends (very approximately) some 15km north-south and 15 km east-west. The area chosen is deliberately large area as our intention is to study Bamburgh as a central place together with its landscape from the prehistoric to the post-medieval period.

MZ: When and how was the cemetery discovered?

GY: The cemetery was discovered in 1817 after a storm stripped away part of the sand dunes which had covered the site in the medieval period. The site was investigated by antiquarians during the 19th and early part of the 20th centuries. Sadly no accurate record of their discoveries was kept. Its exact location was lost by the middle of the 20th century and not re-discovered until we identified our first burials on the site in 1998.

MZ: Since we have a global readership that may not be familiar with this region, what is the landscape like on the Bamburgh headland and where does the cemetery fit into the landscape?

GY: Bamburgh lies on the coast of Northumberland in the far north-east of England. The coastal plain in the area is relatively flat with a series of volcanic outcrops. The castle itself occupies a dolorite plateau which rises some 30m above the surrounding ground. The burial ground lies in the margins of the dunes some 300m south of the castle. The western side of the cemetery is formed by a low sandstone ridge. The north and east sides by low lying ground which is often waterlogged. We are at present engaged in identifying the southern extent of the cemetery. Much of the present dunes system has been deposited in the last 400 years so the cemetery probably lay on a ridge immediately above the foreshore in the Anglo-Saxon period.

MZ: How has the topography of the entire area changed since AD c. 500?

GY: The site is now remote from the sea by some few hundred metres of sand dunes and foreshore. The dune field, however, has been derived substantially from coastal drift in the post-medieval period. In the Anglo-Saxon period the eastern side of the burial ground probably lay quite adjacent to the forshore. This raises the possibility that part of the burial ground may have eroded into the sea.

MZ: How many graves do you estimate there are and how large in terms of area is the cemetery?

GY: If we extrapolate the density of burials in the trenches to the known area of the site we estimate something in the region of a 1000 burials. The extent of the cemetery identified at present is 70m north-south by 40m east-west.

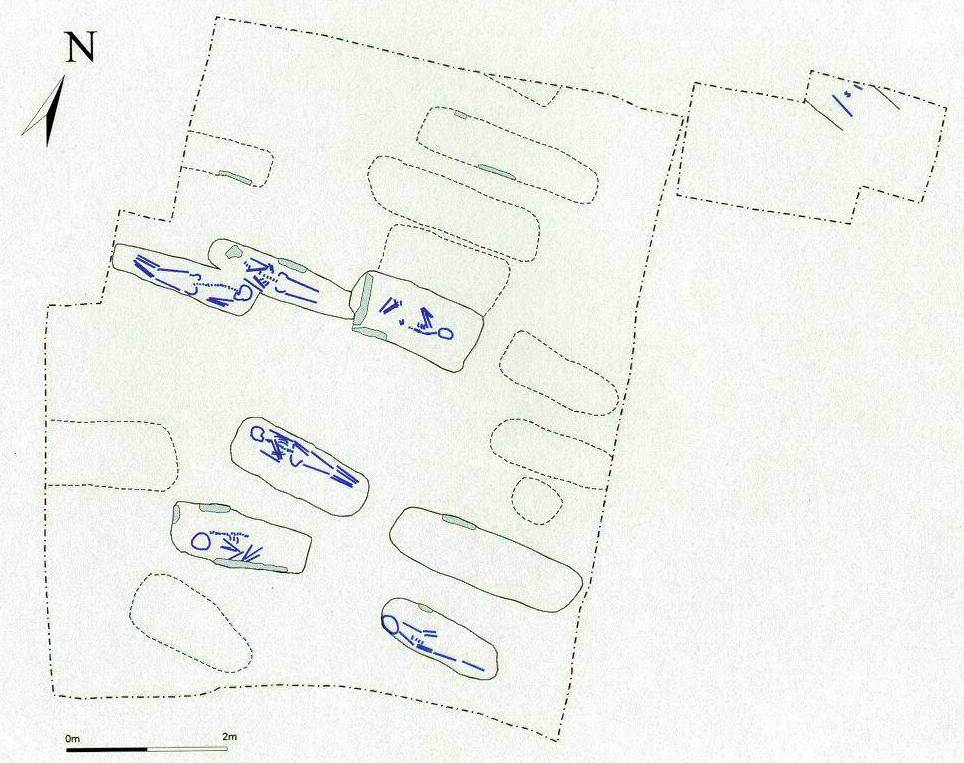

| Diagram of the excavation site with an outline of the trench and directions of the burials. Click on the diagram or here for an enlarged view. |

MZ: Have you seen any continuity between these graves and those found earlier at Yeavering or other Bernician sites?

GY: It is fair to say that some of the Bamburgh burials would not look out of place set beside those at Yeavering and those found as secondary burials around the Milfield henges. It must be said however that our present state of knowledge concerning late British and early Anglo-Saxon burials in Bernicia is so limited as to make any comparisons very speculative.

MZ: Can you give us a date range for the cemetery?

GY: At present due to the presence of long cist burials we envisage the cemetery dates back to the 5th or early 6th centuries and is British in origin. The Anglo-Saxon phase continues at least into the 8th century and possibly later. This is the latest carbon 14 date for a burial at this time.

MZ: How early does the archaeological evidence suggest an Anglian presence at Bamburgh?

GY: We will need carbon dates from a large number of burials to answer this question. At present we don't have a burial which can be dated back as far as the mid 6th century, the time when the Anglo-Saxons are said to have arrived at Bamburgh.

MZ: Are there any other signs of early settlement before or contemporary with the long cist graves. What is the date range for the burials you do have?

GY: The two carbon dates we have at present are 560 to 670 and 640 to 730 both at 95.4 percent probability. Neither of these are primary burials from the British phase of the cemetery. Other long cist cemetery sites have origins in the 5th century. This may well be the case here. They are seen as indicative of early Christianity therefore pre-Christian burials are likely to follow a different burial tradition. The are Bronze Age barrows in the field to the west of the cemetery. These may have attracted much later burials or indicate that the area was associated with the disposal of the dead for a long period. There is clearly scope for a great deal of work in the future.

MZ: How many burials have been found and what percentage of the cemetery has been excavated?

GY: There is evidence

for c20-30 cut graves (they are difficult to identify with certainty

without excavation of the suspected cut). Six graves have been

fully excavated and have produced evidence for at least eight

skeletons, two of the graves being deliberately re-used causing

the disturbance of the original occupant. The six graves represent

very approximately 1 percent or less of the graves in the cemetery.

MZ: Can you give us a description of the variety of graves found?

GY: We have a varied

mixture of burial styles: simple Christian style west-east dug

graves, a west-east flexed cist burial, an east-west crouched

cist burial and an east-west prone burial. There are also at least

three different alignments on an east-west general theme.

MZ: How do you distinguish between British pagan, British Christian,

Anglian pagan, and Anglian Christian graves?

GY: We have one grave with grave goods which suggests a pagan influence. This does not necessarily rule out a Christian context however in a era when kings were known to set up altars to Christ and Woden in the same temple. A simple west-east burial without grave goods could be interpreted as Christian, however unaccompanied west-east burials are known from pagan period cemeteries elsewhere. A great deal of analysis and probably further excavation will be needed before we have a working model that we can apply with any confidence.

MZ: Could you elaborate a little on these body positions? To me, a prone position means extended and face down. What is the difference between a flexed and crouched position?

GY: Three of the six intact burials were extended on their backs face-up, with the head to the west (one dated AD640 to AD730). One was extended face down with the head to the east. One was flexed (or crouched - same thing) on the right side with the head to the west (dated AD560 to AD670). The last flexed on the right side with the head to the east.

| Photo of two graves from the Bamburgh cemetery. The arrow is pointing to a pillow stone of the supine burial. The skull from this grave was lost to erosion. The prone grave has cut into the preexisting supine burial. |

MZ: What types of artifacts have been found in and around the graves? What proportion of the burials excavated to date have associated artifacts?

GY: Two of the west-east

burials on their backs had small quantities of animal bone close

to the skull. Only one burial (that dated 560-670) had artifacts,

a knife and a buckle. A copper or bronze pin was found disturbed

in the topsoil. The cemetery could not be described as finds rich,

but this fits in well with its nature.

MZ: What is the age and sex distribution so far?

GY: A number of the burials are in a poor state making interpretation of age and sex difficult. Six burials were uncovered relatively intact. Of these four were adult males and one adult female, the remaining a juvenile of uncertain sex. There was considerable evidence for arthritic conditions in a number of the adults, suggesting they live to a reasonable age. We will have more information when the analysis of the skeletons is completed.

MZ: What is the state of preservation you are finding for most of the burials and how will this effect your analysis?

GY: The graves are cut

through a sandy soil into boulder clay. The clay is quite acidic

and can cause destruction of the bone which is in close contact

to it. This can result in varied bone preservation within a grave.

The majority of the grave fills are however predominantly sand

which preserves the bone in good condition.

MZ: Is there any indication that the graves were marked with surface memorials or markers?

GY: Intercutting between the graves was seen but was not commonplace. Given the density of burials it seems likely that the burials were marked on the surface. In the case of the long cist graves their stone lining slabs were intended to be seen at the surface and to demark the burial as high status.

MZ: If the stone lining slabs of the cist were intended to be seen on the surface, how shallow was the grave?

GY: The cist burials are preserved in the order of half a metre deep but there is evidence of surface erosion so they were probably slightly deeper in their original form.

MZ: Is there any indication of how long the British long cist cemetery was in use?

GY: Probably from the arrival of Christianity north of Hadrians Wall (c. 5th century AD) to the take over by pagan Anglo-Saxons. The nature of this transition is going to be of particular interest.

MZ: Would the British long cist graves have still been visible during the Anglian occupation?

GY: Yes. When the sand was blown off last century down to the old ground surface they were clearly visible as cists even in this late period.

MZ: Have you found any evidence of a mixed Anglo-British tradition or of the influence of Irish Christianity practiced at Bamburgh from c. 635 to 664?

The fact that the cemetery originated as a British long cist cemetery later taken over by the Anglo-Saxons, would strongly suggest a connection between the two burial traditions. Whether the continued use of the British cemetery by their Anglo-Saxon successors was intended as a political statement of continuity by a new regime or represents the survival of much British cultural tradition is not at present clear. The relationship between the British and Anglo-Saxon elements of Bernician society is a fundamental part of the research we are undertaking. Stable and radio isotope analysis of the teeth from the burials, currently being undertaken, will we hope shed a great deal of light onto the subject of the origins of the individuals concerned.

We are lucky in that Iona lies in a very narrow geographical band between oxygen and strontium within the British Isles. Any individuals who spent their formative years there should show up very clearly. In addition it will be possible to identify any incomers from southern England or continental Europe. Such evidence for the origins of individuals based on a proven scientific technique will greatly improve on the present situation were interpretation is primarily based on the very limited historical record for the period.

MZ: Can you elaborate a little on the types of stable and radio isotope analysis available for modern archaeologists and the types of information such analysis can provide?

GY: The isotopes used are oxygen, lead and strontium. They are laid down in the tooth enamel (and elsewhere in the body obviously but the tooth enamel provides the best material for modern sampling) during childhood. Oxygen reaches the body via the water they drank. The distribution of the variation of isotopes is a climatic variable, in a crude sense a measure of mean temperature. In the northern hemisphere it represents a north to south gradient but in the case of Britain runs south-west to north-east due to other influences such as the Gulf Stream. Strontium is an indicator of the underlying geology. The mineral composition of the soil is dependant on the geology of a region. Food, either crops or grazing animals move the element through the food chain up to humans. Strontium being very similar to calcium gets laid down predominantly in the bones and teeth. Lead is particularly useful in the pre-metal age but can be used to identify exposure to metals which has implications for status. An isotopic distribution map of Britain has been compiled by the British Geological Survey. The measured levels within the tooth enamel of an individual can be compared with the distribution to give in some instances very close correlation with where an individual spent their childhood.

MZ: What has the isotope data on these skeletons revealed?

GY: Of the six skeletons excavated one was without a head due to later erosion of the grave, therefore no teeth! The other five were processed for oxygen, strontium and lead. Samples were taken of the local water and soil to provide a base level for the immediate vicinity of Bamburgh.

None of the five grew up in the Bamburgh area. All bar one which I shall come to later were consistent with soils based on slightly older geology. Taken with the oxygen distribution it would indicate origins in either west Northumberland, Cumbria or the Borders region, consistant with the wider area of Bernicia. One of the skeletons was a child with both permanent and milk teeth. These indicated that this individual had moved within Bernicia as the milk teeth and permanent teeth had different values and neither were for Bamburgh. So this individual had spent their early years at one location then moved during later childhood and a third time to Bamburgh where they were buried.

Our take on this at present, and it is just a working hypothesis, is that the cemetery is a high status one and that only aristocratic burials are located there, hence no local villagers. The royal centre acting as a focus for high status individuals from around Bernicia. The lead values somewhat support this as they are somewhat elevated, consistent with high exposure to metals. Paul Budd has suggested that it may be due to eating of silver plate, as silver is derived from lead sources. In any case the metal exposure is too high to be easily consistent with a normal rural community of the early medieval period.

The last set of data is for the individual buried with the knife and buckle and dated by Carbon 14 at between 560 to 670 AD (at 2sd). The knife has been dated, stylistically, as mid to late 7th century. Taken together this would suggest an actual date in the first two thirds of the 7th century. The oxygen and Strontium values for this individual are very specific and place his childhood either in a small area of Scotland centred on Iona or in a small pocket of the north of Ireland. Given his date and the possible Iona connection it is hard not to see this individual as a Dalriadic Scot who had taken up with Oswald during his exile and returned to Northumbria with him. I am sure there are many other ways of explaining this data, but linking him with Oswald is rather compelling!

| Photo of the skeleton of the 560-670 AD male whose isotope levels place his childhood among the Irish. Click on the photo or here to enlarge the view. |

MZ: Another possibility is that this last man was an Angle born in exile to a parent who accompanied Oswald and his siblings to Dalriada. He could also have been half Dalriadic.It is interesting that the knife would suggest that he was not an churchman. What can the arrangement of his burial and the artifacts tell us about him? Stylistically, which ethnic group does the knife and buckle belong to? Can his age be estimated beyond "adult" and are there any signs of injuries?.Are flexed burials common among the seventh century Irish?

GY: The Iona individual (burial 130 lower left) could be an Anglo-Saxon born in exile but is as likely to be Dalriadic. He was over 40 years when he died (45+ by dental aging) and died no later than the late 7th century, so he could have been born in exile c620 and have died in his 40s before 670. He would be just about making it under the line with this interpretation so him being native Dalriadic is the more likely. Just to complicate things a bit more there are also references, in I think the Annals of Ulster, to Anglo-Saxon exiles in Ireland c600 so before even Oswald. I recall at least two historians speculating on the possibility that Oswald had Christian Irish warriors fighting on his side at Heavenfield, and that they attributed his success to his Christian conversion giving him access to allies that his pagan brother Eanfrith did not have. Our friend had very bad arthritis by the time of his death but no other pathologies that marked the bone.

The knife is correct for an Anglo-Saxon cultural group but I am not sure if Irish knives would be particularly different. The nature of the burial, flexed with grave goods would be consistent with Irish traditions from this period. There are certainly similar burials in the early Christian period in Ireland. Irish archaeologists attribute the style as being introduced from British traditions in the 5th or 6th century. There is clearly a danger of developing entirely circular arguments here when looking for parallels!

MZ: You mentioned that the isotope data for four individuals suggests a Bernician origin. Can you distinguish Bernicia from Deira by the isotope levels?

GY: The oxygen isotope data rules out any of the tested individuals being from as far south as Yorkshire and the Strontium values being for old geology confirm this. So no Deirans.

MZ: Is there any reason to suspect that one or more of these four individuals could belong to the British period?

GY: We only have two carbon dates at this time. Only one, our man above, is from a cist and in that case a re-used one (a separate skeleton had been disturbed and replaced with the backfill), so it is still likely that the cist burials are British in origin.

| Photo of the stone lined cyst after the flexed 560-670 AD male was removed. Bones in the lower end of the grave are of the first, possibly British, occupant of the grave. Click on the photo or here to enlarge. |

MZ: If we can turn toward the Castle for just a moment where I know there have also been recent excavations, what are the prospects for finding remains of the British and Anglo-Saxon fortress under the current later construction?

GY: Hope-Taylor may have found such traces, he claims a pottery sequence back to the Iron Age in his trenches in the West Ward of the castle. He has not published and I feel it unlikely that he will in his lifetime. Our excavations have been too limited to date to draw any firm conclusions for this early period but a ground penetrating radar survey of the Inner Ward of the castle has identified the possible presence of a crypt beneath the remains of the 12th century chapel. We believe this to be the site of the 7th century church and that the crypt very likely dates from this period and could have been associated with the display of St Oswald's relics.

I would like to thank

Graeme Young for being so generous with his time for this interview.

I wish him and his team the best of luck with continuing excavations.

I will be watching eagerly for new information on both the cemetery

and castle projects.

Notes:

1. The Historia Brittonum references are from section 61 and 63. (Hopkins and Koch 1995:282-283) For an online reference, see the Medieval Sourcebook, Historia Brittonum page.

2. A "Ratho" is a fortress in Irish. According to Irish saga, Fiachna mac Báetáin went to Scotland to aid Dalriadic king Aedan mac Gabran against Æthelfrith King of (Anglian) Bernicia. While he was away his wife conceived the Irish hero Mongáin whose father was the sea god Manannan mac Lir. Mongáin was the central figure in a whole cycle of Irish stories. According to the Annals of Tigernach, he was slain by a Briton on Kintyre in 625. The annal entry quoted in the text is dated to 623, but if it really refers to the same incident the annal is misplaced from c. 603. Another Irishman, Máel-Umai son of Báetáin mac Muirchertaig fought in alliance with Aedan against Æthelfrith of Bernicia in the battle of Degsastan in 603 and slew Æthelfrith's brother. (Byrne 1973:111-112).

Bibliography

Byrne, Francis John (1973) Irish Kings and High-Kings. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Hopkins, Pamela S. and John T. Koch. translators. (1995) "§ Historia Brittonum: Excerpts from the Welsh Latin History of the Britons" p. 270-285 in The Celtic Heroic Age: Literary Sources for Ancient Celtic Europe and Early Ireland and Wales. 2nd edition. John T. Koch and John Carey, Editors. Malden, Mass: Celtic Studies Publications.

Further Readings on this topic:

Residence and Religion in the Anglo-Saxon Northfrom Archaeotrace.

For the early medieval history of Bamburgh see:

Bede The Ecclesiastical History of the English People

Farmer, David. ed., The Age of Bede. Penguin. This book contains hagiography of Cuthbert, Ceolfrith, Wilfrith, and the abbots of Wearmouth and Jarrow.

Nennius Historia Brittonum

Kirby, David. (1991, Rev. ed. 2000) The Earliest English Kings. Routledge

To set the archaeology in context see:

Hope-Taylor, Brian (1977) Yeavering: An Anglo-British Centre of Early Northumbria. HMSO.

Hawkes, J. and Mills, S., Editors. (1999) Northumbria's Golden Age Stroud.

Elizabeth O'Brien (1999) Post-Roman Britain to Anglo-Saxon England: Burial Practices Reviewed. BAR British Series 289.

|

|

|

|