|

The Heroic AgeIssue 4Winter 2001 |

Abstract: The evidence for occupation at the Roman fort site of Cramond between the fourth and tenth centuries A.D. is assessed using a variety of sources of evidence including artefacts, place-names, documents and the location of later structures. It is argued that this evidence suggests both British and Anglo-Saxon occupation. Although its exact nature is unclear, a religious element is likely.This article was amended by the author on February 20, 2001.

Contents:

The nature of the Anglo-Saxon impact in southern Scotland has

traditionally been dominated by documentary sources and to a lesser

extent place-name studies. More recently archaeology has begun

to influence how we understand this phenomenon. Whilst much of

the impetus for this has come from recent excavations such as

Whithorn (Hill 1997),

Dunbar (Holdsworth 1993),

and the Mote of Mark (Laing

1973, 1975; Longley 1982), a considerable

amount of information can be gained from older excavations. Although

the evidence from older excavations is problematical it can be

of significance when critically reappraised.[1]

Until relatively recently Roman fort sites were generally excavated

in a manner unlikely to aid the understanding of post-Roman phases

of occupation. We are therefore forced to rely upon stray finds

of artefacts and other sources such as place-names, documentary

sources, and the location of later Medieval structures to attempt

to understand any post-Roman occupation of such sites.

|

|

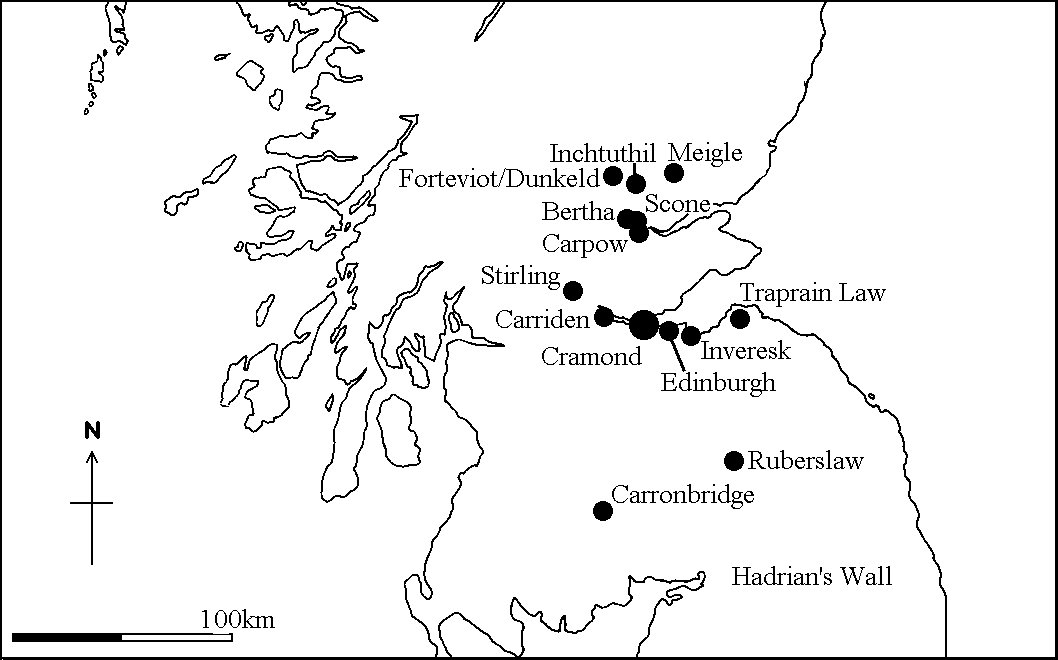

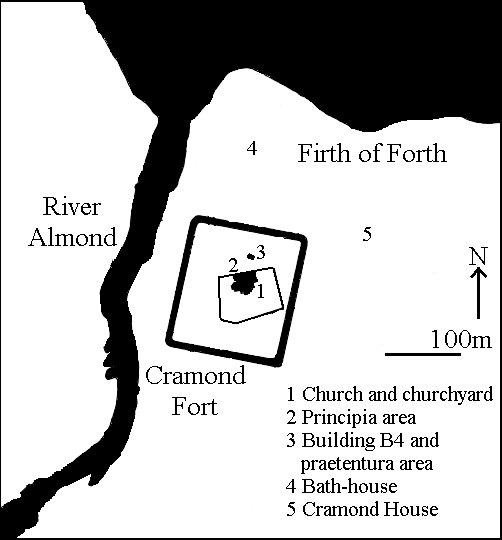

The Roman fort at Cramond, Lothian [NT 189768], on the south side

of the Firth of Forth next to the river Almond, was an important

military base during the Antonine occupation of Scotland (c. A.D.

140-190) and the early third century Severan campaigns. The fort

was probably garrisoned during the Severan occupation from A.D.

208 to 210, and is likely to have been evacuated in A.D. 211 or

212. Its importance did not end at this time, and there is a considerable

body of evidence for post-Severan activity at Cramond that probably

continued until the end of the first millennium A.D. The exact

nature of this occupation is unclear but can be partially reconstructed.

Occupation of the fort during the later third and fourth centuries

has long been recognised as a possibility (MacDonald

1918:214, 216). In the praetentura area of the fort

a stone building, designated B4, was constructed re-using red

sandstone ashlar from the Severan principia and sealed

a coin of Julia Domna (A.D. 196-211) (Rae

and Rae 1974:184-86). The exact date of construction is unclear,

but it probably belongs to the first half of the third century.

The building was crudely made of stone bonded with clay with a

floor consisting of a hard tread of stones, cobbles, and dried

mud. It appears to have possessed glass windows. The unskilled

nature of the construction and the crudity of its floor were interpreted

as suggesting that this structure did not indicate a further period

of Roman military occupation, but it was seen as sophisticated

enough that it could not be dismissed as squatter occupation.

Other post-Severan structural activity has been discovered at

the bath-house to the north of the fort, where furnaces were inserted

and there was some late third-century pottery (Frere

1977:368-70; Grew 1980:354).

This phase at the bathhouse is comparable to the activity at the

praetentura, as it also has crudely built stone walls bonded

with clay. The bathhouse was eventually deliberately dismantled,

suggesting that the site was still occupied after the bathhouse

went out of use. It is now thought that the evidence from the

bathhouse and praetentura may relate to a short phase of

small-scale Roman military occupation immediately postdating the

general abandonment of the fort in A.D. 211/212.

Both building B4 and the bathhouse produced late third-century

Roman pottery indicating continuing contacts with the Roman province

to the south. There is also a general scatter of pottery of this

date from other parts of the fort and the nearby vicus (Goodburn 1978:418; Rae and Rae 1974:217-18).[2]Such contacts are also

indicated by a number of Roman coins. The site has produced coins

of Geta (A.D. 211-12), Caracalla (A.D. 211-17), Tetricus II (A.D.

270-73/4), Probus (A.D. 280-81), Diocletian (A.D. 284-305), Galerius

(A.D. 305-11), Constantine I (A.D. 306-37) and Constantine II

(A.D. 337-61) (Bateson 1989:167;

Robertson 1983: table

2).[3]These coins are

all stray finds but do appear to indicate continued activity throughout

the third and first half of the fourth centuries.

Stray finds of post-Severan coins from Scotland are a problematical

source of evidence (Casey

1984; Robertson 1983:429-30).

The evidence from Traprain Law clearly shows that the Votadini

continued to have access to Roman coins throughout the third and

fourth centuries (Sekulla

1982), so there is no a priori reason to discount the

coins from Cramond. Casey suggests that coins from western mints,

particularly Trier and Lyons, are more likely to be genuine, but

this can not be taken as an absolute criteria (Casey

1984; see also Bateson

1989). Some of the coins from Cramond are of particular interest:

the coin of Tetricus came from the spoil heap associated with

the bathhouse excavations and was minted at Cologne; as it comes

from a western mint it may well be genuine (Robertson

1983:408). Much of the bathhouse was robbed to foundation

level in the seventeenth century and subsequently large quantities

of soil and associated debris were dumped on the site. Much of

this material may have come from some distance away, so that some

of the later third- and fourth-century artefacts may not be associated

with the bathhouse at all. Even if this is accepted, the material

must still have come from somewhere on the Roman fort or the civilian

settlement. Coins of Diocletian, Galerius, and Constantine I were

all found in close proximity during the digging of a garden at

15 Glebe Road and are described as having an "emphatic"

provenance (Robertson 1971:115-16),

although only the coin of Constantine, from Arles, is from a western

mint. This collection--which comes mainly from eastern mints,

does not include any Severan or earlier coins, and was found in

association with a later Byzantine coin (see Later

Artefacts below)--probably represents a modern loss.

Excavations in the 1970s uncovered some poorly preserved structural

remains indicating a short-lived immediately post-Severan phase

of activity on the site; they also produced some pottery indicating

post-Severan activity (pers. comm., Nicholas Holmes 1998). The

excavator interpreted this as indicating that there was some native

re-occupation of parts of the site and that Roman patrols probably

continued to visit the site throughout the third century, but

there was no evidence for activity after the late third century.

>From the patchy evidence that has been recovered, it seems that

activity continued at Cramond throughout the third century and

possibly into the first half of the fourth century. The nature

of this occupation is unclear and difficult to interpret, but

it indicates that Cramond was not completely abandoned during

the third and fourth centuries.

Although no structural remains of the Early Historic period (A.D.

400-1100) have been found at Cramond, a number of artefacts of

this period have been discovered. There is a bronze coin of the

Byzantine emperor Justinian (A.D. 527-65) (Robertson

1971:115-16), which was discovered in the same location as

some post-Severan coins discussed previously. Although most Byzantine

coins from the British Isles are dismissed as modern losses (Casey 1984:295), there

is evidence for trade between the eastern Mediterranean and western

Britain and Ireland c. A.D. 475-550 that penetrated as far north

as central Scotland (Alcock

and Alcock 1990; Fulford

1989). There is therefore no reason to automatically discount

the coin of Justinian from Cramond, although the coins that it

was discovered with suggest that it may well be a modern loss.

Another discovery was an eighth- or ninth-century enamelled bronze

circular mount with equal-armed cross decoration incorporating

millefiori and yellow champleve enamel discovered in the

churchyard at Cramond, which overlies the fort (Bourke

and Close-Brooks 1989:230-32).[4]

This was probably originally part of a larger composite Insular

object, probably ecclesiastical. A plain bronze finger ring discovered

at Cramond in 1870 whilst digging a grave near the church bears

an Anglo-Saxon runic inscription "[.]ewor[.]el[.]u."[5 ]The letters "wor"

are best interpreted as part of the Old English word worthe,

"made," and the rest of the inscription probably consisted

of one or two Anglo-Saxon personal names. Although it has been

suggested that this item is ninth century, it is not closely dateable

and the only thing that can be said with certainty is that it

probably dates to between the second half of the seventh century

and the tenth century (Laing

1973:18; Page 1973:36).

A blue glass bead found near Cramond House (PSAS

1970: no. 10) is not closely dateable, but such items are

typical of Early Historic Celtic sites.

These various stray finds from in and around the fort suggest

that it continued to be a focus for activity until at least the

eighth or ninth centuries. The enamelled mount in particular suggests

a site of some wealth and importance. The lack of structural evidence

hinders any interpretation. It is unclear from the archaeological

evidence if the site was continuously occupied and whether it

was a secular or religious site.

The place name Cramond is not recorded prior to the twelfth and

thirteenth centuries, when it is found in a number of forms such

as Caramonde/Caramonth (A.D. 1178-79), Karramunt (A.D. 1166-1214),

and Karamunde (A.D. 1293) (Nicolaisen

1976:162; Watson 1926:369).

The name contains the distinctive Brythonic or P-Celtic element

cair/caer, which means "fort," plus the river

name Amon, whose exact linguistic roots are unknown (Nicolaisen

1976:160-62, 178). Cramond therefore means "fort on the

river Almond," and the name must have originated prior to

the conquest of this area by Anglo-Saxon Northumbria in the middle

of the seventh century.

The earliest part of Cramond parish church is the fifteenth century

tower, although parts of the building incorporate fourteenth century

masonry (RCAHMS 1929:27-28,

no. 37). It is located over the praetenturna of the Roman

fort, as are a number of other parish churches in Scotland including

Carpow and Inveresk (Smith

1996:24). This might be dismissed as coincidence, but as the

praetenturna was a focus for post-Severan activity and

the churchyard produced an Early Historic enamelled mount, this

suggests that the administrative centre of the Roman fort retained

some form of administrative or religious importance during the

Late Roman and Early Historic periods.

There are a number of possible documentary references to Cramond.

Bede (EH I.8; Colgrave and

Mynors 1991:40-41) refers to a site known as Urbs Giudi

in the early eighth century, and the same site is referred to

as Iudeu in the tenth century Historia Brittonium attributed

to Nennius. Historia Brittonium describes events in the

650s, when king Oswy of Northumbria was defeated by an alliance

of Penda of Mercia and some British kings at the urbem,

"city," of Iudeu and forced to hand over the Atbret

Iudeu, "treasure of Iudeu" (Morris

1980:38, 79). There is also a reference to the merin iodeo,

"sea of Iodeo" or Firth of Forth, in the Gododdin

poem (Jackson 1969:108;

Jarman 1988: line 944),

and Iodeo is probably the same as Iudeu. Guidi/Iudeu has sometimes

been equated with Cramond (Hunter-Blair 1947:27-28; Rutherford

1976:443) but opinion now generally favours Stirling instead (Alcock 1981:175-76; Jackson 1981; Jarman

1988:147, n. 944). There are two important pieces of evidence

against the identification of Guidi/Iudeu with Cramond. Firstly,

as it possessed a significant Roman past, Bede would probably

have termed it a civitas rather than an urbs (Campbell 1979). Secondly,

as the defences had been slighted and the ditches filled, the

site would not have been easily defensible. It is therefore unlikely

that Oswy would have retreated there when pursued by his enemies.

Another documentarily attested site is Rathinveramon, where two

kings died. Domnall, son of Alpin, rex Pictorum-king of

Picts-was killed in A.D. 862; and Constantine, son of Culen, ri

Alban-king of Scotland-was slain by Kenneth, son of Malcolm,

in A.D. 995.[6] The

deaths of two different kings in the ninth and tenth centuries

suggest that this was an important site. The first element in

the name Rathinveramon, which means "fort at the mouth of

the river Almond," is the Goidelic or Q-Celtic element rath,

which means "fort." Rath is an uncommon place-name

element for Scotland and refers to a site with a bank and ditch.

O. G. S. Crawford (1949:60)

believed that rath indicated a Roman fort and equated Rathinveramon

with the Roman fort of Bertha in Tayside, and this has generally

been accepted.[7] There

are, however, two river Almonds in Scotland: one in Tayside, beside

which Bertha is located; and one in Lothian, which flows past

Cramond. It is therefore conceivable that Rathinveramon is Cramond

rather than Bertha, a suggestion that has been made previously

(A. Anderson 1922, 1:518).

Rathinveramon is in fact the Goidelic equivalent of the Brythonic

name Caramonde. It is conceivable that the Scottish Goidelic-speaking

incomers adapted and gaelicised the existing Brythonic place-name.

The evidence for activity at Cramond at this time, in the form

of the eighth- or ninth-century enamelled mount and possibly the

ring with runic inscription (see Later

Artefacts above), supports this suggestion. In contrast there

is no evidence for any post-Antonine activity at Bertha (Adamson

and Gallagher 1986:203; Callander

1919:145-52).

The problem is that the documentary sources that mention Rathinveramon

were generally written down several centuries after the events

they describe. This allowed plenty of opportunity for confusion

to arise concerning which of the two rivers Almond Rathinveramon

was sited beside. Such confusion is best exemplified by the fourteenth-century

Scottish historian John of Fordun, who places the events of A.D.

862 in Tayside (IV.15) and those of A.D. 995 in Lothian (IV.34);

this was repeated by the twentieth-century historian Alan Orr

Anderson (1922, 1:291

n. 5, 518 n. 7; 1922,

2:782) when he quotes Fordun. The source with the best claim to

be contemporary is the Annals of Ulster, which do not state where

Domnall and Constantine were killed (MacAirt

and MacNiocaill 1983:318-19, 424-25). In contrast the sources

that seem to provide the most geographical detail are those like

the Prophecy of Brechan, which was not composed until the

1160s and whose reliability is open to question. The river Almond

in Tayside is located in an area that was an important focus of

Early Medieval royal activity with sites such as Scone, Forteviot,

Meigle, and Dunkeld, which encouraged early authors to place Rathinveramon

on the Almond in Tayside, perhaps erroneously. The documentary

sources do not allow an unequivocal decision between the rivers

in Lothian and Tayside, so it is at least possible that Rathinveramon

should be equated with Cramond rather than Bertha.

Edinburgh--Oppidum Eden--and therefore presumably Cramond,

was under Northumbrian control from the mid-seventh century until

the reign of the Scottish king Indulf (A.D. 954-62), when it passed

into Scottish hands apparently without a battle (A.

Anderson 1922, 1:468). When Constantine was killed at Rathinveramon

in A.D. 995, Cramond was under Scottish control and his presence

there is clearly possible. In A.D. 862, when Domnall was killed,

Cramond was still under Northumbrian control. The frontier between

Northumbria and Scotland was, however, probably relatively close

to Cramond and the Scottish kings were closely interested in this

area. Domnall's presence at Cramond in A.D. 862 is therefore quite

plausible.

The exact territorial boundaries of the Votadini are problematical,

the best source being Ptolemy's Geography, but other Roman

forts that the Votadini could have occupied in their heartland

along the southern side of the Firth of Forth were Carriden and

Inveresk. Carriden has not produced any evidence of post-Antonine

occupation during the Roman period, and the next clearly attested

occupation is during the thirteenth or fourteenth century (Bailey 1997). There is

a post-Roman phase consisting of a gully, drain, and post-hole,

which can not be precisely dated; it occurs some considerable

time after the Roman abandonment but prior to the thirteenth-

or fourteenth-century occupation (Bailey

1997:591). This evidence is extremely difficult to interpret

and only further work will elucidate its nature and precise date.

Excavations on both the fort and the vicus at Inveresk

indicate that it was not occupied during the Severan campaigns.[8] In fact there is no

evidence for occupation between the Antonine occupation and the

thirteenth or fourteenth century. Two coins of Gallienus (A.D.

260-68) and Constans (A.D. 341-46) are reported to have been found

at Inveresk (Robertson 1983:408)

but are not mentioned in the excavation report (Thomas

1988:171, fiche 2 A.12-B.1) and must be assumed to be erroneous.

The place-names of Carriden and Inveresk do not retain any elements

that preserve the memory of the presence of a Roman fort. The

fort of Carriden at the eastern terminus of the Antonine Wall,

which also falls within Votadinian territory, might appear to

be derived from Caer Eidyn, but this is problematical. Kenneth

Jackson argued that the early forms of the name such as Karreden

and Karedene can not be derived from this source but David Dumville

has challenged this (Dumville

1994). Even if Dumville is correct his argument suggests that

the name Carriden may be relatively late as he suggests that this

fort was originally named 'End of the Wall' [Penguaul, Cenail,

Peneltun] a topographical descriptive term later applied to

Kinneil and not necessarily indicating any occupation. The third

fort within Votadinian territory was Inveresk. This name contains

the Gaelic element inbhear, "in-bring", denoting

the junction or confluence of a river (Watson

1926:148), and must therefore post-date the Scottish take-over

of the area in the tenth century; in any case it makes no reference

to the presence of the Roman fort.

There is, however, some evidence that the site of Inveresk still

retained some importance. The location of the Medieval church

at Inveresk (see The Medieval Church

above) is suggestive, as are documentary sources which show that

it may have been the "centre of a territorial arrangement"

(Proudfoot and Aliaga-Kelly

1997:40-42). The evidence suggests that Carriden's position

at the end of the Antonine Wall was no longer of strategic importance,

but that Inveresk's position at the end of Dere Street may still

have been significant, although the site itself was probably not

occupied. The continued occupation at Cramond suggests that links

by sea may have been of greater importance than land-based links.

The archaeological, place-name, and documentary evidence suggests

that Cramond was an important site in the post-Severan period,

although its exact nature is unclear. In general Roman forts do

not seem to have been particularly favoured as locations for native

settlements in Scotland, although the evidence is probably not

as negative as suggested by Dark (1992:111,

n. 7), who focused solely on the fifth and sixth centuries. Apart

from Cramond there is evidence for a native fort at Inchtuthil,

Grampian, which re-used Roman masonry (Abercromby

et al. 1902). Perhaps less significant are a ninth- or tenth-century

silver-gilt penannular brooch, iron sickle, and sword found at

Carronbridge, Dumfries and Galloway, as their location at a Roman

fort has been described as "almost certainly coincidental"

(Owen and Welander 1995).

The other Roman fort apart from Cramond with substantial evidence

of Severan occupation is Carpow. While it lacks archaeological

evidence for occupation after the early third century (Birley

1963; Wright 1974),

it is mentioned in an early documentary source as Ceirfuill. The

source refers to a lapidem juxta Ceirfull, "stone

beside Ceirfuill" (Chadwick

1949:9-10), which may relate to a rather later fragment of

a cross-slab from Carpow House (Cessford

1996). Although this does not demonstrate that Carpow was

occupied, it indicates its continuing importance as a focal point

in the landscape. The evidence from Ruberslaw, Borders (Alcock

1979:134; Curle 1905),

is rather different, as the re-use of Roman masonry here involves

a hilltop site and the stone probably came from a signal station

tower rather than a fort.

Most known high-status sites in Scotland of the post-Roman period

are small- to medium-sized hillforts, whereas Roman forts, which

were larger, were probably too large for the requirements of the

period. They were also not located in naturally strong defensive

sites. There are, however, a number of important undefended sites

of this period, the most notable being Forteviot, Tayside (Alcock and Alcock 1992:218-41).

The continued activity at Cramond and other Roman forts may be

of a similar nature to Forteviot. Roman forts were located at

nodal communication points on the Roman road network, which probably

continued in use during the early Medieval period, and in the

case of Cramond the site was also well situated with regard to

communications by sea. Such forts also acted as quarries of raw

materials, notably for stone but also nails, glass, coins, and

other artefacts that were re-used during the early medieval period

in Scotland. Their history and a lingering sense of romanitas

may also have meant that controlling Roman fort sites provided

a source of authority and legitimacy to native dynasties.

Dark (1992; see also

Snyder 1996:47-48) has

suggested that the evidence of fifth- and sixth-century refurbishment

of defences, timber halls, inscribed tombstones, and Germanic

artefacts at forts on Hadrian's Wall indicates that they were

reused as part of a still-functioning military frontier with high-status

British occupation and the use of Germanic mercenaries. Whilst

there are certain similarities between the sub-Roman evidence

from Hadrian's Wall and that from Cramond, Dark's model appears

unsuitable for Cramond. There are no indications that the defences

at Cramond were still functional after the Severan period or that

there was a military presence at the site, so a martial interpretation

is difficult to substantiate. The enamelled bronze circular mount

and the location of Cramond parish church both suggest that there

was a religious component to the occupation at Cramond. The most

likely scenario is that ownership of the fort at Cramond passed

into the hands of the native dynasty of the Votadini after its

abandonment by Roman forces. There is no evidence that occupation

of the site was continuous and what the discoveries may instead

reflect is a continuity of royal ownership. Cramond was probably

controlled by a succession of royal owners in a manner similar

to that suggested for some Roman forts in England, where churches

occur from the seventh century onward (Bidwell

1997:108-9). The site continued in use after the Anglo-Saxon

take-over of the region in the early seventh century and may have

remained in use throughout the Anglo-Saxon occupation until the

tenth century. It is even possible that the Scots subsequently

occupied it.

The evidential basis for assessing the Early Historic occupation

at Cramond is fragmentary and open to a range of interpretations.

Nevertheless, given the focus upon substantial Roman structures

during previous excavations at the site combined with the frequently

insubstantial nature of building remains and the general lack

of dateable artefacts during the Early Historic period in Scotland,

the body of evidence that does survive is perhaps as much as might

reasonably be anticipated. Cramond appears to be a potentially

important site for understanding the complex interactions and

transitions between different political and ethnic groups in Northern

Britain during the second half of the first millennium A.D. If

its identification with Rathinveramon is correct, it is a site

where events of considerable historical significance took place.

Recent work on Hadrian's Wall has shown the potential for careful

excavation of Roman fort sites to uncover the less obvious evidence

for later periods of occupation and it is to be hoped that this

will eventually be repeated at Cramond.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|